Encounters with Cedar

Cedar trees define Prince of Wales in sweeping freeform strokes that bring softness to the landscape, their branches hanging low to kiss incoming ocean tides, bark soft, roots sprawling and open. Yellow cedar grow throughout Southeast Alaska, but the range of red cedar doesn't extend as far north. Prince of Wales is one of the few islands in Southeast Alaska that is home to both species.

Aiken Cove. Sandhill cranes take flight from the beach grass. Their ancient music is in my ears as I follow a well-stomped bear trail into the forest. When I see the pink flagging, sharp comprehension turns quickly to rage for everything that has happened to this island. It takes a moment before I see the tree standing directly behind the focal point of my anger; it's been standing here since before the United States was founded.

The mark of timber cruisers was everywhere; it seemed that whenever we started coming into big trees we'd either hit a clearcut or flagging.

Thorne watershed. Shattered trees spread across a recent clearcut. Cedars don't fall cleanly; the straight cut of the chainsaw goes against the nature of the tree. Splinters like bone. Mara and I are silent, lingering, but the light is low, and with few words exchanged we heft our packs and continue to look for a campsite.

Klawock. Viking mill. Mechanized grasping. The humans stationed at levers are breathing the dust of 500-year-old cedars. This mill represents most of the timber industry on Prince of Wales, and they're milling mostly cedars these days. About half the trees are cut and sent by barge-load to Viking's de facto parent corporation in Washington state, the others are sent round-log across the ocean to Asia.

last trees standing

Cedar trees are the new target on Prince of Wales. They're the last trees standing, but as their market value increase, so does the rate of cut.

There are still some big beautiful spruce trees between Moira and Chomondeley.

First it was spruce. Much of the spruce on Prince of Wales was cut during the era of the pulp mills, from the 1950s to the early 90s. Spruce grows tall, straight, and in dense stands--easy pickings for the voracious pulp mills. Cedar trees are more sparsely distributed on much of the island, but the areas where they're dense have until now been relatively untouched by the timber industry.

We experienced this when we hiked from Moira Sound to Cholmondeley Sound. Moira Sound was the densest cedar that we saw during Last Stands, and also the most intact and wild place we saw (though there was plenty of timber cruiser flagging marking the big trees). After exploring Moira Sound, we hiked north to Cholmondeley. It was a day hike, and as we made our way north we started to encounter exceptionally tall and beautiful spruce trees. Almost as soon as the forest was predominately spruce, we found ourselves in a clearcut.

Now that most of the spruce are gone from POW, and the market for cedar has improved, the cedar is next the target of the timber industry.

Southeast Alaska naturalist Richard Carstensen joined us for the final week of Last Stands. Photo by Lee House

The loss of ancient beings

My friend Richard Carstensen joined Mara and I for the last leg of our Prince of Wales trek. Richard is one of the best naturalists in Southeast Alaska, and a seriously legit groundtruther (check out his d-rating for bushwhacking in Southeast AK). He's been thinking about cedar trees for years, and has been disturbed by how aggressively they're being targeted on Prince of Wales. He helped me understand a couple of things about cedar: (1) once we cut them, they're not going to grow back, (post clearcut, cedars won't be able to compete), and (2) They're the most ancient trees in Southeast Alaska, and we need to consider their value as longstanding and irreplaceable giants in our forests.

Before he joined us on Prince of Wales - while we were still thrashing about in the backcountry of Moira Sound - Richard emailed us this idea about what it means to cut down ancient cedar:

"The way I've tried to characterize the magnitude of loss is to ask what we're cutting/exporting not in terms of volume but in terms of the years of tree growth it took to produce these ancient beings. By that metric, we may be hemorrhaging worse right now than during the peak years of volume export in the 50s and 60s."

Unfortunately cedar trees on Prince of Wales will be cut for as long as we continue to prop up a timber industry in Southeast Alaska. The Last Stands team hiked through lands threatened by the 2-million acre public lands giveaway - a transfer that would allow for devastating clearcuts with zero public process - but the same lands are also threatened under current federal management. The USFS is in the midst of developing a 15-year plan for Prince of Wales, and prominently featured in this plan is the extraction of between 170 and 425 million board feet of old-growth in the next 15 years. This means that nearly half of the remaining old-growth on Prince of Wales could be cut by 2033.

For a hard-hitting critique of the Forest Service's plan, check out this incredibly detailed scoping comment from the Alaska Rainforest Defenders.

Two cedar trees and me. Tuxekan, POW

A return to Cedar

This is one of the first posts that I've written since spending a month in the backcountry of Prince of Wales. Adventure in a conflicted landscape of home is more emotionally exhausting then I should even attempt to describe in this blog. It's taken time, but I've recently found the energy to return to my notes, recordings, and photographs.

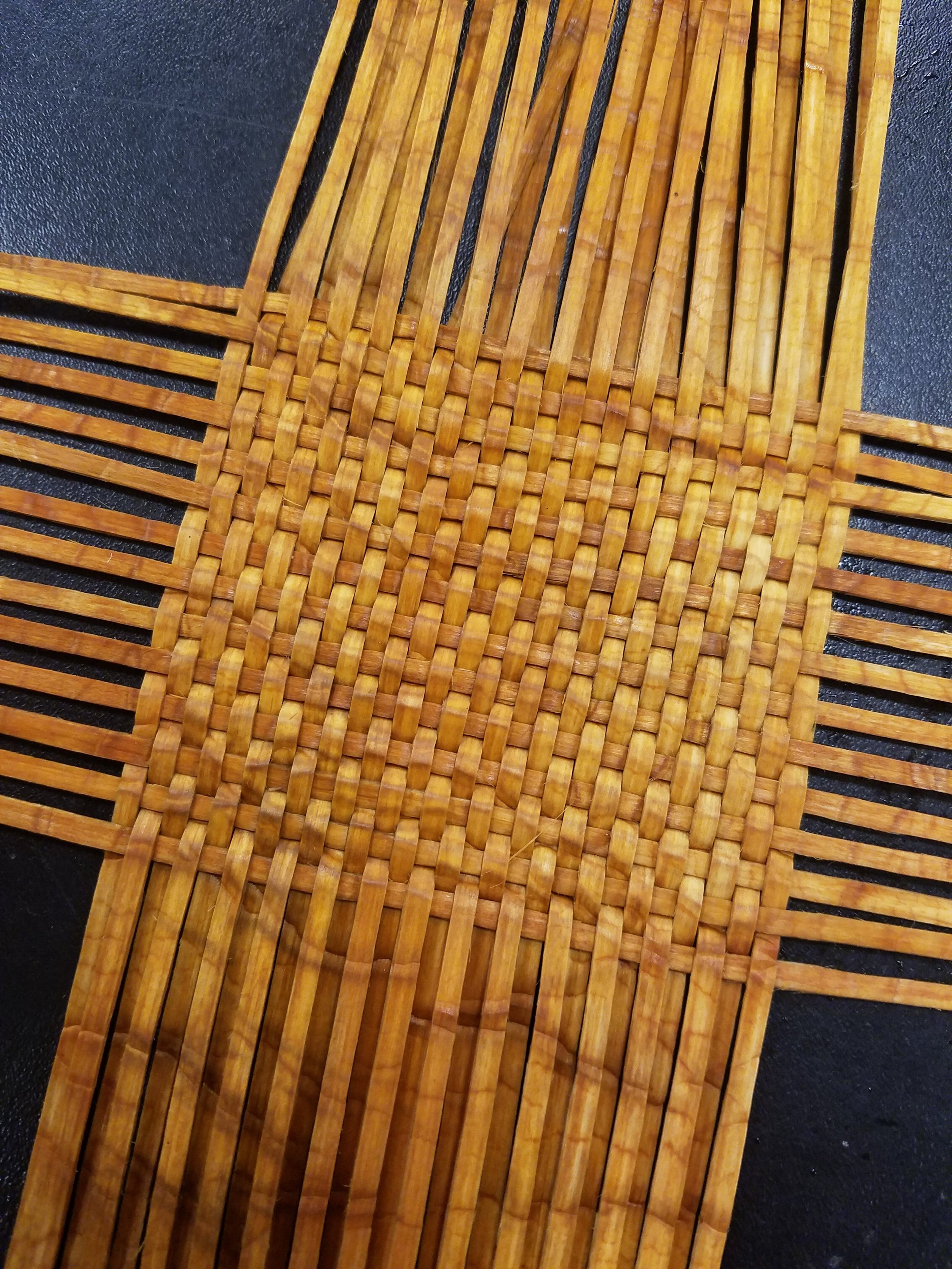

I've also found my hands working damp fragrant cedar in a weaving course with Haida master weaver Delores Churchill. I'm making a basket with cedar stripped from trees on Prince of Wales. Red cedar forms the base and structure of the basket, and the more supple yellow cedar is woven around the red.

Old Tuxekan

After Natalie, Mara and I hiked our longest transect - across the island from Karta River to Tuxekan - we were feeling fairly disheartened by human impact on the island. It wasn't just the clearcuts, but the haphazard way that they consumed the landscape. The decades of clearcutting and logging roads followed no natural order, the land felt confused, untended, choked and dark with second-growth and entirely inhospitable to animals (whether they be black bears or humans with backpacks).

When we did make it to the western shores of Prince of Wales we unexpectedly found ourselves in a special place. The Tlingit village site of Old Tuxekan. Everywhere there were living cedars with distinct features of a long-held relationship to humans. Some trees had been stripped for weaving bark, and others had been investigated by adz for their totem or canoe potential. We all relaxed into a place that seemed relatable, and as we were reminded of how short the history of reckless exploitation on this island has been, we shook the murmur of hopelessness that had dogged us for much of the cross island trek. This island continues to be known as Taan (sealion).

Living cedar tree, once stripped for bark.

Living cedar tree, once explored for canoe or totem potential with adz.

Before Last Stands...

In my last week of frantic preparations for Last Stands, my dear friend Louise Brady - kik.sadi Tlingit playwright, activist, grandmother, herring protector - emailed me a recording of a poem she was working on. Her words of homecoming and love offered more guidance on my Taan trek than the gps clipped to my belt. There has always been love. The history of greed is short on Taan, the cedar trees remember a time when things were different.

Louise Brady